January 2nd 1979 was a cold day in Scotland. The harsh winter snows meant that the crowd at the famed annual missionary “Report Meeting” in Harley Street Gospel Hall, Glasgow, was much smaller than usual. However, those present were to witness something they would never forget. One of the three missionaries to speak that day was Robert Crawford Allison (1911-1979), a very ill man only 9 months from his homecall to heaven. He had just had a major operation, and had to sit while he spoke. But here was a man who had laboured for the Lord in central Africa for 44 years, travelled tens of thousands of miles, learnt 13 languages, survived multiple bouts of malaria, including cerebral malaria, avoided death on several occasions including being held at gunpoint. How was this possible when he left School at 14 to become a bricklayer? Listen to learn what God can do with a life wholly devoted to Him.

January 2nd 1979 was a cold day in Scotland. The harsh winter snows meant that the crowd at the famed annual missionary “Report Meeting” in Harley Street Gospel Hall, Glasgow, was much smaller than usual. However, those present were to witness something they would never forget. One of the three missionaries to speak that day was Robert Crawford Allison (1911-1979), a very ill man only 9 months from his homecall to heaven. He had just had a major operation, and had to sit while he spoke. But here was a man who had laboured for the Lord in central Africa for 44 years, travelled tens of thousands of miles, learnt 13 languages, survived multiple bouts of malaria, including cerebral malaria, avoided death on several occasions including being held at gunpoint. How was this possible when he left School at 14 to become a bricklayer? Listen to learn what God can do with a life wholly devoted to Him.

Below is a biography of Robert Crawford Allison, taken from the book They Finished Their Course“, published by John Ritchie Ltd, Kilmarnock, Scotland, in November 1980.

Bobby Allison was born in the little town of Galston in the Irvine Valley in Ayrshire, Scotland, in 1911. His father was a colliery winding engineman who was in fellowship with the “Needed Truth” company of the Lord’s people that met in the town. His mother, Barbara kept open house and an open Bible. Bobby was saved when he was a lad of 14.

Early in his Christian life he showed an interest in missionary work although that company of Christians with which he was associated showed little interest in it. When he confided his desire to his mother, when he was 17, she was thrilled and told him her own secret. She too had wanted to be a missionary but her state of health had prevented her dream being realised. When her son was born, she coveted that kind of life for him and wanted to call him Crawford Robert Allison after the great Scots missionary in Central Africa [Dan Crawford] but father’s wishes had prevailed and his name was Robert Crawford Allison.

A few years later, three young men from that company of Christians in Galston attended an open air Missionary Conference in a field in nearby Newmilns, beside the outdoor stairway called Jacob’s Ladder, and heard Andrew Borland speaking on John 10:16: “Other sheep I have which are not of this fold: them also I must bring, and they shall hear my voice; and there shall be one flock and one shepherd.” Those young men were excommunicated from the “Needed Truth” group for being at that conference, but two of them became missionaries; Willie Templeton who gave his life for the Lord in Trinidad, and Bobby Allison who spent most of the rest of his life in Africa. [Having left School at 14] Bobby was already an apprentice bricklayer, a trade which he was able to use to good advantage in Africa. Conscious of his lack of education Bobby began taking help in English from the late George Borland, and this facilitated his language learning in years to come. He anticipated working with primitive peoples and therefore took a course in dentistry. As far as the spiritual side of life was concerned, he was happy with the instruction received at the weekly conversational Bible Study in the Evangelistic Hall, Galston. Years later, when asked what seminary he had attended, Bobby would tell of the profit derived from attending the assembly Bible Study.

In 1930, at a Missionary Conference in Ayr, Bobby heard T. Ernest Wilson of Angola, at home for his first furlough, describing the needs of the unevangelised tribes in the north of that country, and became interested. His first move was to Portugal in 1934 to learn Portuguese. He was only there a few months when his mother’s death caused him to return home. In 1935 he set out with the commendation of the Galston assembly to try to meet that need.

The first two years were spent immersing himself in the culture and thinking of the Songo and Chokwe peoples, as well as learning their languages. In 1937 his bride arrived, Margaret Haggerty, daughter of an innkeeper in the Irvine Valley. Their honeymoon was a 1,000 mile trek to Saurimo where they were to make their home for a number of years. It was around this time that Bobby contracted the illness [malaria] which dogged him till the end of his days and which made Margaret so indispensable to his work. He had triumphed over lack of education; he would now have to triumph over physical disability which brought him to death’s door several times, and which required hospitalisation in Cape Town, Salisbury, Glasgow, Edinburgh and London.

It was about this time too that he came to be called Crawford. Close-knit communities can’t have people called by the same names. There was already a fellow-Ayrshireman called Robert in Angola, Robert McLaren, so that Bobby was called by his middle name, which was of considerable significance to Africa and indeed to himself, in view of his mother’s wishes expressed earlier.

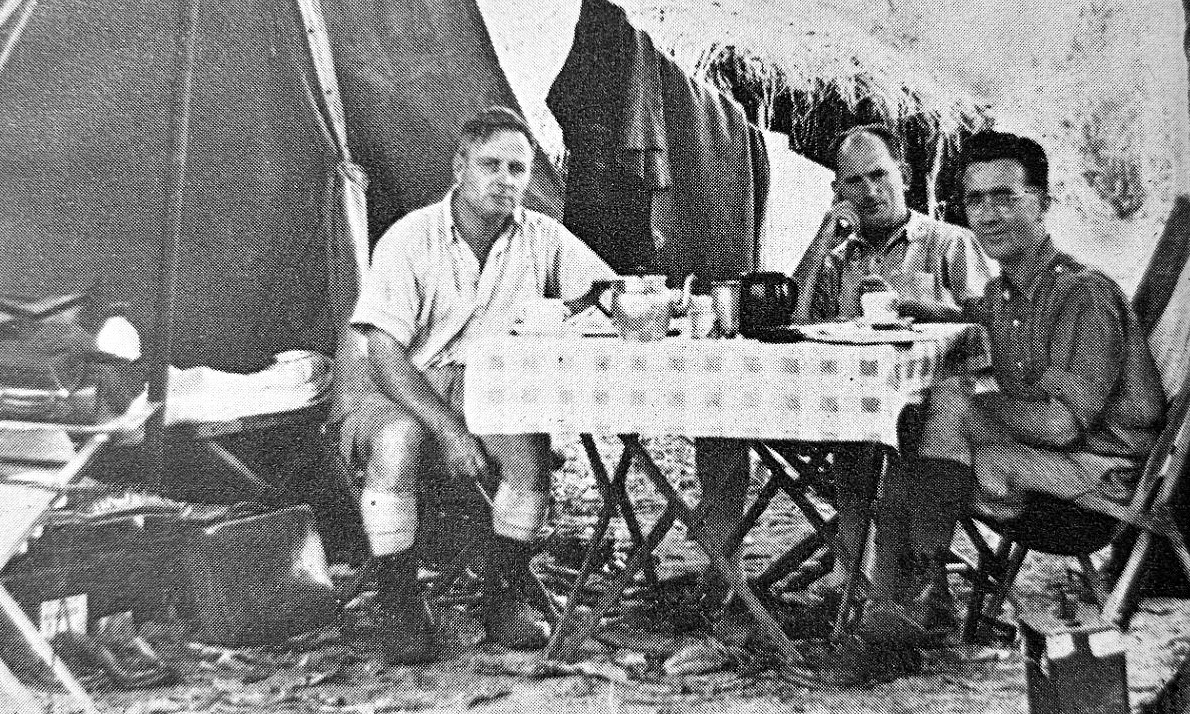

The early years were spent trekking among the tribal villages of central and eastern Angola. The Second World War broke out only two years after their marriage. For most of a year after Dunkirk, there were no communications of any kind from the homeland, and their children had arrived. It was thrilling to hear the story of the Lord’s provision when they first came on furlough after the war, ten years after Bobby had first gone out.

But Bobby’s heart was set on reaching those unevangelised tribes in N. Angola. And so with others, especially George Wiseman, they spent months pioneering among the Shnji, Mbangala, Minungu, Ruunda and N. Chokwe. Between 1948 and 1957 Allison and Wiseman made 17 trips of over 1,000 miles over indescribable roads to help these new believers who were being saved and baptised in their thousands. Today there are hundreds of assemblies among the Shinji, comprising thousands of believers shining brightly among the darkness of paganism, animism and Marxism. Shortly before he was called home he whispered to his family at his bedside, “When I see a Shinji believer in heaven, that will make it two heavens for me.”

When inability to obtain a visa for Angola, and his ill-health, prevented a return to Saurimo, Bobby Allison didn’t lie down and give up. He simply transferred his home to Salisbury, Rhodesia [now Zimbabwe], which was to become the base for even wider missionary movements. At his farewell in Prestwick, Scotland, he recalled, with a lump in his throat, that those whom he had pointed to Christ were being martyred in Angola. He also announced his dream of seeing a new circle of assemblies being formed as it became increasingly impossible for missionaries to return to the “Beloved Strip”. That circle would stretch from Malawi through Rhodesia/Zimbabwe and Mozambique into Botswana. This circle would be greatly aided by some other missionaries whose call had come as the result of hearing his reports: Willie Hastings, who served first in Angola and then along with him in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, and Jim Legge, pioneer in Malawi and nurse with his wife, Irene who were with him for the last weeks of his earthly life.

The new vision required this sick man to learn several more languages, so that the gospel could be spread and New Testament churches planted among the Shona, Chewa, and Sena tribes. His pioneer spirit took him to the remote parts of the Zambesi Valley, to Botswana, to Mozambique before a communist government took over and closed the door, and to Malawi “in the trail of Livingstone” as he would have said. In each of those countries there are many rich trophies of grace that have been won for the Master. The last report mentioned the existence of over 40 assemblies in communist-controlled Mozambique.

Much of his work was due to literature distribution, an activity which can continue even without the long treks of white missionaries. Bobby Allison wrote a series of tracts based on his great knowledge of the Bantu mind. The first converts in several areas were made through reading Christian literature and Bobby Allison was only too happy to do the follow-up work.

When he came home it was generally for medical treatment. Travelling to give reports of his work was restricted. He generally sat while he spoke. He couldn’t eat and drink at the same meal. During his last furlough, a recording studio was built on to his house in Salisbury. It was a pity, he said, to have so many languages and not use them. The British winter of 1978-79 was dreadful and it was a very sick man who made his way back to Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, out of it. He did want to be with his Africans at a critical time in their history and he wanted to die among them.

During those ten months before the Lord called him home he achieved something more. One of his last letters said, “After many teething troubles in our recording work we have now been able to record the first messages. Two of them we recorded in the Chewa language for Malawi. Then two in Shona for Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, followed by another two in Chokwe for Angola…We had to take time to teach two of our African brethren to speak the messages into the mic, while one of our missionary brethren does the monitoring and looks after the recording machines. The first two messages in Chewa were taken to Malawi by our full-time evangelist, Manuel Chisale, when he went two weeks ago. A three-day conference was held at Blantyre which was well attended, not only by the local Christians, but by many from the bush assemblies. Manuel was able to play back the two messages which we had made in Chewa.”

His last letter, dictated a fortnight before the Lord called him home, was ended in typical fashion, “Yours in the train of His triumph”. His son, David added this footnote about his father, “He taught us how to live and now he is teaching us how to die.”

His son David wrote, “To the Scots folk who supported him so faithfully, both practically and materially over the years, he was known as Bobby. To English-speaking Africa and to America he was known as Crawford. To the Songo he was known as Ngala, to the Chokwe, Shinji, Mbangala, Minungu and Ruunda he was Ngana. To the Shona he was Mufundisi, to the Chewa and Sena he was Muphinzitsi. To the Tswana he was Moruti and to the Portuguese he was simply Senhor.”

Andrew Borland, a fellow-Galstonian kept in touch with him during all of his missionary life. Hugging the frail figure about to leave for Africa again at his last farewell meeting he recited the following of his own composition.

Calling, calling, ceaseless calling,

That Beloved Strip, held dear

And I can’t refuse the answer,

To the voices that I hear.

Still another voice is calling;

‘Tis the voice of One I love;

And I go to seek for others

For his Father’s House above.

All I ask as I leave you,

That for me you’ll often pray;

Pray that God will give me fitness

For the tasks of every day.

Pray for health of mind and body,

Pray that triumphs may be won;

And you’ll share the Master’s praises,

You will hear, “Well done, well done”.

I can hear strange voices calling,

Quite unheard by untuned ears;

But, though silent, coming urgent

Down the corridor of years.

They have all one common message,

Undesigned, yet strangely one,

Telling of the wondrous vict’ries

Messengers of Christ have won.

Comes the voice of Robert Moffat,

Scotland’s early pioneer,

Toiling ‘mong the backward Bushmen,

Living with them without fear.

Facing death from beast and native,

Faint with fear oft and sore,

David Livingstone is calling,

Dying, praying on the floor.

I can hear lone Stanley Arnot

Call from Garanganze wild,

Trusting God for daily guidance,

Trusting like a little child.

From Luanza, Konga Vantu,

Greenock’s Crawford, Thinking Black,

Calls with unmistaken accents,

Beckoning my footsteps back.

Treading in the warrior’s pathway,

Was John Wilson, Ayrshire bred,

Short, his faithful service calls me,

Lives his voice, though long since dead.